Open Science

Version 1.0

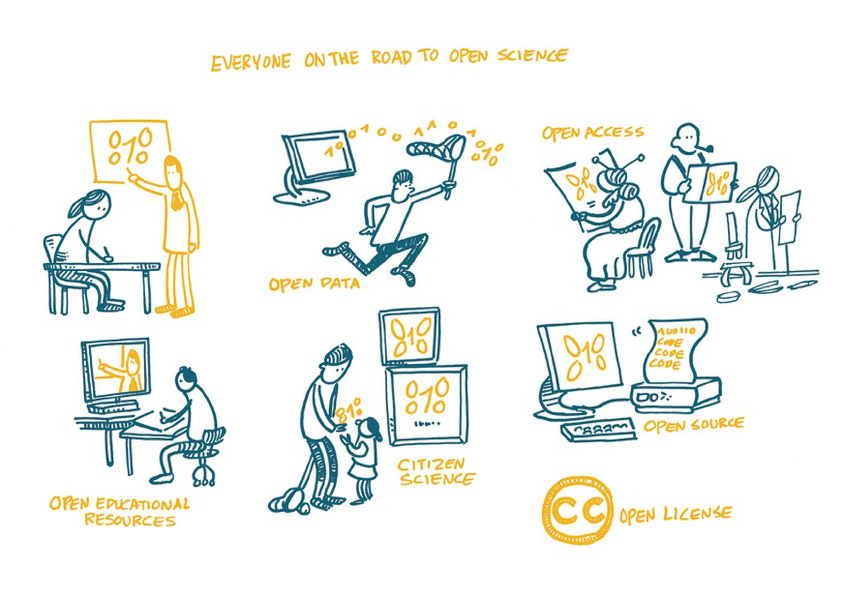

Open science is a rather broad umbrella term, and generally refers to making research accessible to and reusable by the wider scientific community and general public. As shown in Figure 1, Open Science is multifaceted. This document focuses on those aspects that are currently most relevant for the Ctrl-ImpAct lab, namely Open Data, Open Source and Materials, Open Methodology and Transparency, and Open Access.

Figure 1: On the road to Open Science (By Patrick Hochstenbach CC BY 4.0)

Why do we care?

In psychology, the Open Science movement is strongly linked to ‘psychology’s renaissance’ 1. More specifically, Open Science and increased transparency are often presented as solutions to problems such as poor reproducibility and questionable research practices. For example, Open Data and Materials allow other researchers to rerun analyses (i.e. analytical reproducibility), check to what extent conclusions depend on decisions made during the analysis phase (i.e. how robust are the findings?), and help the field establish the replicability and generalisability of the findings. Open Methodology, and preregistration in particular, can help with issues such as p-hacking, harking, and publication bias. Thus, Open Science practices can help us (further) reduce various biases in research.

As demonstrated by other disciplines, a much more positive case for Open Science can (and should) be made as well. For example, in 2016, Florida became the epicentre of the first reported Zika outbreak in the USA. This raised all sorts of research questions, which could only be answered through collaborative research and open science 23. Similar examples exist in other disciplines, such as astronomy 4. There is no good reason why such coordinated and open research efforts cannot be possible in psychology. For example, rather than sharing genome sequences, mosquito abundance, or sun spots, psychologists can share ratings, norms, databases, etc. Thus, we do not need a ‘reproducibility’ or ‘integrity crisis’ to embrace Open Psychological Science. In fact, the current tools and new technologies make it easier than ever to share data and materials, with potentially great benefits. For example, in times when resources are scarce, Open Psychological Science can help us avoid unnecessary duplication of research efforts. When data are shared, and subsequently combined and integrated, we may also end up with larger and more diverse data sets. Open Science can also encourage and facilitate collaboration, and help us tackle the really big questions.

There is yet another good reason for Open Science. Our research is publicly funded, so one should ask the question of whom the data and materials belong to in the first place: shouldn’t they be considered a public good, rather than the ‘property’ of individual researchers? Indeed, in recent years, there have been calls from governments and research funders for science to be more open. For example, the Amsterdam Call for Action on Open Science 5, published in 2016, highlights two main, pan-European goals. First, there should be full open access for all scientific publications by 2020. This may require new publishing models, which could involve learned societies; we will come back to this below. Second, by 2020 there should also be a fundamentally new approach towards optimal reuse of research data. More specifically, data sharing should become the default approach for publicly funded research. Note that these two goals are most relevant for the Ctrl-ImpAct lab, as we are funded by the European Research Council (ERC). The ERC already requires open access (Goal 1) and we will participate in their Open Research Data pilot (Goal 2)6.

The Ctrl-ImpAct Lab On the Road to Open Science

The Ctrl-ImpAct lab aims to be at the forefront of good research practices and Open Science. In this section, we briefly outline the lab’s main principles, policies and procedures. Links to documents outlining more specific information will be added as these evolve.

Open Data

At the beginning of the project, DMPonline.be will be used to create a Data Management Plan, which is vital to prepare for and implement proper data sharing later on. The general lab rule is that data should be as open as possible, as closed as necessary 7. The FAIR principles 8 will provide further guidance: data of finished projects should be Findable, Accessible, Interoperable (i.e. others should be able to integrate our data with minimal effort), and Reusable.

Fully anonymised and non-sensitive data will be made publicly available via e.g. the Open Science Framework and/or other trusted data repositories9. As outlined in the lab guidelines (which will also be shared via OSF), this will include an experiment documentation file, providing all information that is required to interpret the data files. The data will be published under a CC BY 4.0 licence.

In case of confidential data (e.g. personal or otherwise confidential data), the FAIR principles stipulate that rich metadata should be published to facilitate discovery. Publication of such metadata can also be done via OSF or other appropriate repositories. These metadata will include clear rules regarding the process and conditions for accessing the data. In other words, everybody can find out if the data exist or not, but not everyone will be able or allowed to access and use them (for any purpose). In case of highly sensitive materials or when misuse and abuse are expected, we may have to ask an independent body to arbitrate and decide who gets access and who doesn’t. These procedures will allow FAIRness in the absence of FAIR publication of the data themselves.

Open Source and Materials

Sharing software or research materials with others can help the field avoid unnecessary duplication of research efforts, and may encourage collaborations across labs. It may also increase the visibility of our work, as demonstrated e.g. by the popularity of the STOP-IT software package, which was developed by our lab 10.

All new software developed by the lab will be shared via platforms such GitHub, which has integrations with the OSF and Zenodo repositories for archiving purposes (including assigning DOIs). This can include software required to run experiments or to analyse data (e.g. R scripts or packages). Specialised software will be published under the GNU GPL-3.0 licence. Open Source software or packages that are developed by others should be appropriately acknowledged.

The same principles will apply to stimulus materials developed by the lab. These materials can be shared under the CC BY 4.0 licence. When existing stimulus materials will be used in our research, preference will be given to materials that are free to reuse, modify, and redistribute.

Open Methodology and Transparency

We aim to preregister all our confirmatory, hypothesis-driven experiments. Again, this will be primarily done via OSF. A preregistration should include the following information11:

- Description of the research design and study materials, including planned sample size

- Description of motivating research question or hypothesis

- Description of the outcome variable(s)

- Description of the predictor variables including controls, covariates, independent variables (conditions)

- Description of the analysis plan (procedures, exclusions, further variable construction, tests or models). This information has to be as specific as possible.

Preregistered experiments are submitted and reviewed after data have been collected. In some circumstances (especially when it is expected that the research question can be addressed with a single experiment), we may submit the initial proposal as a Registered Report. Such reports are reviewed before data have been collected, and passing the first stage of review virtually guarantees publication. Several journals (including most of the society-led Open Access journals listed below) offer registered reports.

Of course, we may not always have strong predictions at the start of a study. Furthermore, we agree that serendipity and accidental findings are key factors in making scientific discoveries. Therefore, the lab highly values exploratory (or ‘discovery’)12 science as well. Open Methodology and increased transparency do not prevent such exploratory research; they only require us to label exploratory or post-hoc analyses as such. Furthermore, they require us to describe experimental and analytical procedures in an open, transparent, and sufficiently detailed fashion, allowing others to exactly replicate our work.

Finally, we believe that active and open collaborations are critical for our research. This starts within the Ctrl-ImpAct lab. Even though all lab members typically work on a specific subproject, active collaborations are highly encouraged. Furthermore, we will establish a ‘co-pilot’ system1314. For each, study, there is a lead researcher (or ‘pilot’) and a ‘co-pilot’, who is involved in the entire workflow. The ‘co-pilot’ researcher not only double-checks the data analysis scripts of the ‘pilot’ researcher, but is also involved in other tasks, from the conception of a research idea until the publication of the manuscript. Such collaborative efforts will lead to co-authorships. Our co-pilot system is described in more detail in Reimer et al. (2019).

We will be transparent when it comes to authorships as well, by including in each paper a statement on the contribution of all authors.

Open Access

The ERC, who have funded most of our lab’s research since 2012, mandate Open Access to publications. In psychology, the most popular route to make publications freely available is ‘self-archiving’ of the accepted version of the manuscript (i.e. Green Open Access)15. However, researchers and universities have argued that this is not sufficient because Green Open Access does not challenge the current (overly expensive) publishing models enough 16.

An alternative is Open Access journals. Much has already been said about the pro’s and cons of such journals. On the one hand, Open Access journals can make publicly-funded research widely available. At the same time, publishing in Open Access journals may involve the payment of Article Processing Charges (which in the case of ‘hybrid’ journals enables publishers to ‘double dip’ by charging both APCs and subscriptions), and there are many predatory and low-quality Open Access journals. Yet it would be wrong to throw the baby out with the bathwater. In recent years, we’ve seen that learned societies, research funders, and scientific organisations have started their own Open Access journals 17. Others have proposed the Fair Open Access principles, which can provide further guidance 18. These are very interesting and important initiatives that the Ctrl-ImpAct lab wishes to support.

Therefore, from June 2018 onwards (at the start of the new ERC project), our default policy is to publish our findings in Fair or society-led Open Access journals. But as the Fair Open Access movement is still new and the number of society-led journals is still fairly low, there might be circumstances in which the default policy may not always work (e.g. when the paper is rejected in the preferred Open Access journal or when no other appropriate alternatives are available). In such situations, high-quality Open Access and traditional journals will be considered as well. However, these traditional journals should still meet some minimal requirements; for example, immediate Green Open Access should be allowed (i.e. no embargo period), preferably via institutional repositories (as this allows proper and long-term archiving), and we should retain full copyright 19.

From 2018 onwards, we will publicise on our Publications page what percentage of papers from the Ctrl-ImpAct team is published in open access, learned society-owned journals.

Final Remarks

As outlined above, Open Science has many benefits. But there is no denying that it requires some extra time and effort, certainly at the start of a project. Luckily, these costs can be partly mitigated via online tools and support from peers and institutions. But there might be another ‘cost’ or risk as well. When other researchers reanalyse our data and reuse our scripts or software, they might discover errors. Obviously, we will try to absolutely minimise such errors. At the same time, we should accept that we are human after all, and that errors can happen. Therefore, when errors are spotted, open and honest communication will occur and we will immediately take the appropriate steps to correct them.

Costs or risks associated with good and open science can be mitigated at institutional or research council levels. There are indeed some signs that this is already happening, as indicated by the (slow) shift from quantitative to qualitative evaluation of researchers and projects (e.g. at UGent or the ERC). But there are many things we can do ourselves as well. For example, we can advocate the Open Science agenda when we review papers or proposals, and encourage data or materials sharing or applaud researchers who are already doing so.

And maybe it is just time for psychologists to revalue or embrace ‘slow science’ 20 a bit more. As noted in Nuzzo 21, we should not only further strengthen the accelerators of the scientific process but also the ‘brake’; i.e. “the ability to slow down, be sceptical of findings and eliminate false positives and dead ends”. As researchers studying inhibition and control of impulsive action, we could not agree more…

Nelson, L. D., Simmons, J., & Simonsohn, U. (2018). Psychology’s renaissance. Annual Review of Psychology, 69, 511–534. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-122216-011836↩

https://naturemicrobiologycommunity.nature.com/users/40355-nathan-grubaugh/posts/17015-open-science-combats-zika↩

Open Science also played a critical role in curbing recent Ebola outbreaks; see https://www.nature.com/news/data-sharing-make-outbreak-research-open-access-1.16966↩

https://www.nature.com/news/long-term-research-slow-science-1.12623↩

https://www.government.nl/documents/reports/2016/04/04/amsterdam-call-for-action-on-open-science↩

http://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/data/ref/h2020/other/hi/oa-pilot/h2020-hi-erc-oa-guide_en.pdf]↩

Wilkinson, M. D., Dumontier, M., Aalbersberg, Ij. J., Appleton, G., Axton, M., Baak, A., … Mons, B. (2016). The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Scientific Data, 3, 160018. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.18↩

https://www.allea.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/ALLEA-European-Code-of-Conduct-for-Research-Integrity-2017.pdf↩

All lab members have an OSF account. We encourage everybody to create such a free OSF account to share data and materials.↩

https://osf.io/wuhpv/; see also https://scholar.google.be/citations?user=GfHmv20AAAAJ&hl=en↩

Wicherts, J. M. (2011). Psychology must learn a lesson from fraud case. Nature, 480(7375), 7–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/480007a↩

Reimer, C. B., Chen, Z., Bundt, C., Eben, C., London, R. E., & Vardanian, S. (2019). Open Up – the Mission Statement of the Control of Impulsive Action (Ctrl-ImpAct) Lab on Open Science. Psychologica Belgica, 59(1), 321. https://doi.org/10.5334/pb.494↩

https://ec.europa.eu/info/research-and-innovation/strategy/goals-research-and-innovation-policy/open-science/open-science-monitor/trends-open-access-publications_en↩

See for example https://openaccess.be/2018/05/18/ku-leuven-supports-a-fair-approach-to-scholarly-publishing/#more-9681↩

Possible journals include eLIFE, eNeuro, Royal Society Open Science, or Journal of Cognition. There are several other examples.↩

PNAS might be the most well-known example of such a journal; see Sherpa/Romeo↩

‘The slow science manifesto’. Retried from: http://slow-science.org↩

Nuzzo, R. (2015). How scientists fool themselves – and how they can stop. Nature, 526(7572), 182–185. https://doi.org/10.1038/526182a↩